Food fraud: can we trust the authenticity of our food?

Food fraud poses a serious threat to the food system. How can we fight against it and be confident that the food we are buying is authentic and safe?

As we draw closer to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals of peace and prosperity for people and the planet by 2030, the European agrifood industry is transforming to become safer, healthier, more sustainable and more transparent. However, it is unfortunately not exempt to crime. Fraudulent activities within the agrifood industry are increasing (1) and are damaging the food system. Reported cases of suspected food fraud in EU Member States increased by 85% between 2016 and 2019 (1) and the COVID-19 pandemic is predicted to have increased the presence of substandard goods even further (2).

What is food fraud?

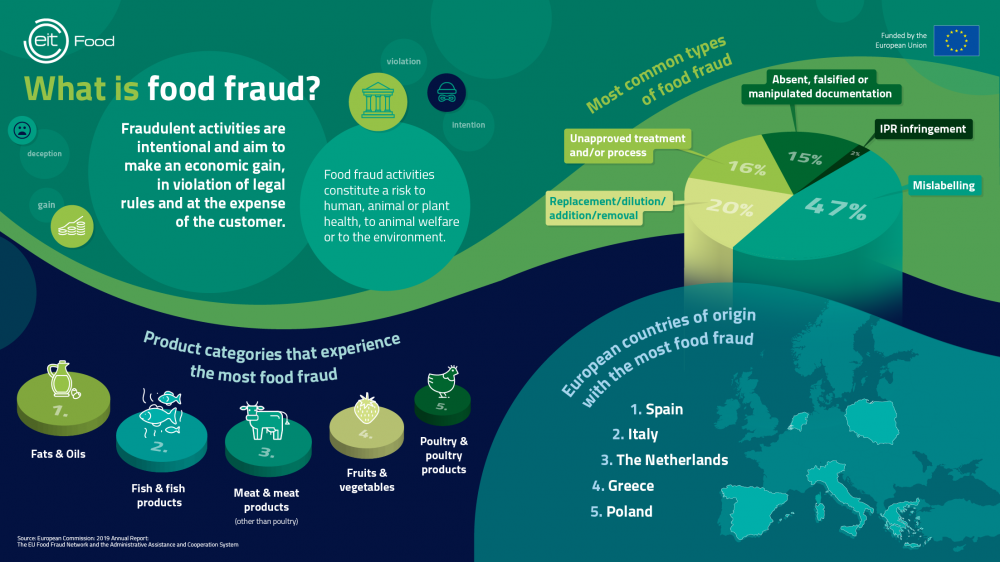

Fraudulent activities are characterised by their intentional nature and end goal of making economic gain. They are in violation of rules, requirements and agrifood chain legislations, and are at the expense of the immediate or final customer, whether it be another business in the supply chain or a consumer. In most cases, food fraud constitutes risks to human, animal or plant health, animal welfare and the environment (1), and ignores moral and ethical principles.

Another risk, as Professor Louise Manning of the Royal Agricultural University explains, is that businesses which comply with the law are forced to compete with businesses who are cutting corners, meaning that they are placed at unfair competitive disadvantage against unscrupulous rivals.

The famous horsemeat scandal of 2013, which saw beef burgers and ready meals fraudulently produced with cheaper horsemeat across the UK, put food fraud in the spotlight in Europe and has acted as the framework for the fight against it ever since (1). The scandal caused consumers to question their trust in the agrifood industry and prompted the establishment of the EU Food Fraud Network (EU FFN), a group composed of the European Commission, the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) and Member State liaison bodies to fight food fraud. The network allows competent authorities to assist and coordinate with one another, sharing knowledge and information as they request assistance when food fraud cases arise.

But food fraud can take many forms and is often difficult to identify. From the dilution of alcoholic beverages to the intentional mislabelling of allergen information, one thing that all types of food fraud have in common is that they are detrimental to the reputation of the agrifood industry and cause harm to consumers and legitimate businesses. In fact, economically motivated food adulteration is estimated to create damage of around €8-€12 billion per year (3).

Food fraud is also often part of wider criminal activity. As Professor Louise Manning notes, crime groups that are involved with food smuggling and food trafficking “might also be involved with people trafficking and other illicit activities too. These networks can be truly global so it is essential that we have regulatory checks at border inspection points, such as at the point of entry into the European Union.”

What is the state of food fraud in Europe?

Due to the complexity and vast global reach of modern food supply chains, food fraud is categorised by its country of origin. Sorting cases by country aims to create a clearer picture of where fraudulent activity actually occurs so that the appropriate authoritative action can be taken at a local level. Within Europe, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands are reported to have the most cases of food fraud, with fats, oils, fish, meat, fruits and vegetables and poultry the most adulterated food product categories (1).

In a bid to reduce these figures, Europol and INTERPOL coordinate the annual OPSON operation to target the trafficking of counterfeit and substandard food and beverages in Europe and beyond. In the midst of the pandemic, the 2020 operation seized illegal products across all food categories including 320 tonnes of smuggled or substandard dairy products, 149 tonnes of cooking oil and 1.2 million litres of smuggled alcohol (4).

Food fraud during COVID-19

OPSON 2020 also confirmed ‘a new disturbing trend’ linked to the infiltration of low-quality products into the supply chain - a development that the operation linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (4).

The pandemic is thought to have catalysed fraud across the entire world. From websites selling artificial COVID-19 tests to the seizure of substandard facemasks, counterfeiters have been quick to profit from the COVID-19 outbreak, and food has unfortunately been no exception. Europol suggested that some criminal groups may have seized opportunities during the crisis to offer counterfeit or substandard food items both online and more widely following fears of food shortages (5). It was also discovered that large quantities of artificial and potentially harmful food and vitamin supplements were entering the EU market in 2020 as criminal groups took advantage of the increased focus on personalised nutrition and health during the pandemic (2).

With furloughed staff and a reduction in governance, the COVID-19 crisis may also have reduced some scrutiny on food products moving through the supply chain, allowing more food fraud to occur. Selvarani Elahi MBE, UK Deputy Government Chemist and Business Manager for Food Research, said “it is likely that the true impact of COVID-19 on the incidence of global food fraud will not be known until full resumption of regulatory surveillance worldwide. In the meantime, the food industry must be extra vigilant and continue to use the available existing best practice authenticity control measures and tools.”

"We’ve had food fraud since the beginning of time and it is likely to continue. If there is a competitive advantage to a given behaviour in the food supply chain, and a perceived lack of deterrence or an unlikely potential for detection, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there will always be a motive to behave badly.”

What is being done to mitigate and prevent food fraud?

“There is a whole range of activity that is being undertaken to combat food fraud,” says Professor Louise Manning, but while the majority of food safety organisations and regulators have recognised food fraud as a serious problem, there are concerns that few have laid out concrete systems and processes for how to address it (6). It is therefore crucial for the agrifood industry to come together to share ideas and best practice about food fraud mitigation and prevention. A great example of this is the Food Authenticity Network, a public-private organisation that gathers information on food authenticity testing, food fraud mitigation and food supply chain integrity, and then shares it via its open access website. This means that stakeholders can share best practice and advice, helping to raise standards worldwide.

According to the EIT Food Trust Report, which surveyed almost 20,000 European consumers about their trust in the agrifood industry, only 40% of people have confidence that the food products they buy are generally authentic (7). This represents a huge opportunity for the agrifood industry to innovate and work alongside consumers to build trust and increase transparency - and reduce fraud as a result.

One way that reducing food fraud can be achieved is through networks such as the EU FFN and the Food Authenticity Network, but the use of technologies is another. Digital traceability systems such as blockchain can help to track a food product’s journey through the supply chain and pinpoint the origins of food fraud. This is why EIT Food supports entrepreneurs who are innovating to increase transparency and traceability through technologies like this. EIT Food RisingFoodStar SwissDeCode, for example, has created a DNA test that allows food producers and farmers to rapidly prove the authenticity and safety of their food products, ensuring that fraudulent food does not enter the supply chain.

But technologies alone cannot prevent food fraud. An integrated approach must be taken in order for all types of fraud to be eradicated from the supply chain. “Individual food businesses need to develop their own risk assessments to reduce vulnerability and make sure they are embedding all the necessary controls in their business,” explains Professor Louise Manning, who highlights that deterrence, controls, surveillance and responsiveness are the key elements that will reduce the risk of food fraud.

How can you join the fight against food fraud?

Raising awareness about how to identify food fraud, and subsequently expose criminal groups, is another method to reduce risks and increase confidence. Handbooks and guides such as the Food Integrity Handbook on Food Authenticity Issues and Related Analytical Techniques, which is a result of European collaboration through the EU-funded FoodIntegrity project, are a great way to for industry stakeholders as well as consumers to keep up to date with the latest protocols, assessment techniques and food fraud risks.

Education initiatives such as EIT Food’s online Future Learn courses, which give consumers and stakeholders the chance to learn more about trust, food safety and the complexity of supply chains in a flexible and personal way, are also critical to raising awareness. The free courses include:

- Understand Food Supply Chains in a Time of Crisis

- Food Integrity Matrix: The 4 Key Elements

- Trust in Our Food: Understanding Food Supply Systems

- Understanding Food Labels

- Farm to Fork: Sustainable Food Production in a Changing Environment

As new foods such as alternative proteins become more mainstream, and as crises such as climate change and COVID-19 challenge society, the opportunities for counterfeiters to take advantage of the food system rise. Therefore, food fraud mitigation and prevention is as much about industry and policy intervention as it is about awareness, collaboration and consumer knowledge. Only by coming together can we reduce food fraud, improve consumer trust and make the food system safer.

Further reading

- EIT Food: Food Safety Eurobarometer: 50% of Europeans rank food safety among their top three food-buying priorities

- New Food: Food fraud – one of the big winners during the COVID pandemic

- EIT Food: Food Fight podcast: Is our food safe?

- FoodUnfolded: Food fraud: when does food become criminal?

- European Commission: Food fraud: what does it mean?

References

- European Commission: 2019 Annual Report: EU Food Fraud Network (EU FFN) and the Administrative Assistance and Cooperation System

- Europol: Viral marketing – Counterfeits, substandard goods and intellectual property crime in the COVID-19 pandemic

- European Commission: Food fraud

- Europol: 320 tonnes of potentially dangerous dairy products taken off the market in operation OPSON IX targeting food fraud

- Europol: Viral marketing: counterfeits in the time of pandemic

- FoodUnfolded: Food fraud: when does food become criminal?

- EIT Food: The EIT Food Trust Report

About The Author: EIT Food

EIT Food is Europe’s leading food innovation initiative, working to make the food system more sustainable, healthy and trusted.

More blog posts

POWERED BY A PARENT’S LOVE

Connecta2Invest: connecting capital with agrifood tech innovation