How can we all fight childhood obesity?

In the past 40 years, childhood obesity has become one of the world’s most serious public health challenges, and a recognised problem in every country in Europe.

Since the 1970s, the number of obese school-age children and adolescents has increased by more than 10 times (1). In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 124 million children were obese globally, and a further 216 million were overweight (1).

In Europe, obesity rates are as high as one in five for boys (20%) in some southern countries. Northern countries tend to fare better, but some still have high rates. In Sweden, for example, 10% of boys and 7% of girls are obese. (2)

Childhood obesity can deeply damage children's physical and mental health and can be associated with poor academic performance and a lower quality of life experienced by the child (3).

What’s more, 60% of obese children are also obese as adults (4) and are more likely to develop a variety of health problems including cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, musculoskeletal disorders and endometrial, breast and colon cancers.

What causes childhood obesity?

The causes of the increase in childhood obesity are complex. EIT Food’s Innovation Programme Manager Mercedes Groba, who is currently leading a series of workshops seeking to find the measures most likely to slow the growth and reduce the condition, says: "Right now, the world is at a turning point. Childhood obesity has been with us for a long time, and we know that the ideas tried so far haven't really worked. We need to look at all the elements of modern life that influence the issue and come up with new, culturally-appropriate solutions. There are many causes, and we need to look at how they interact."

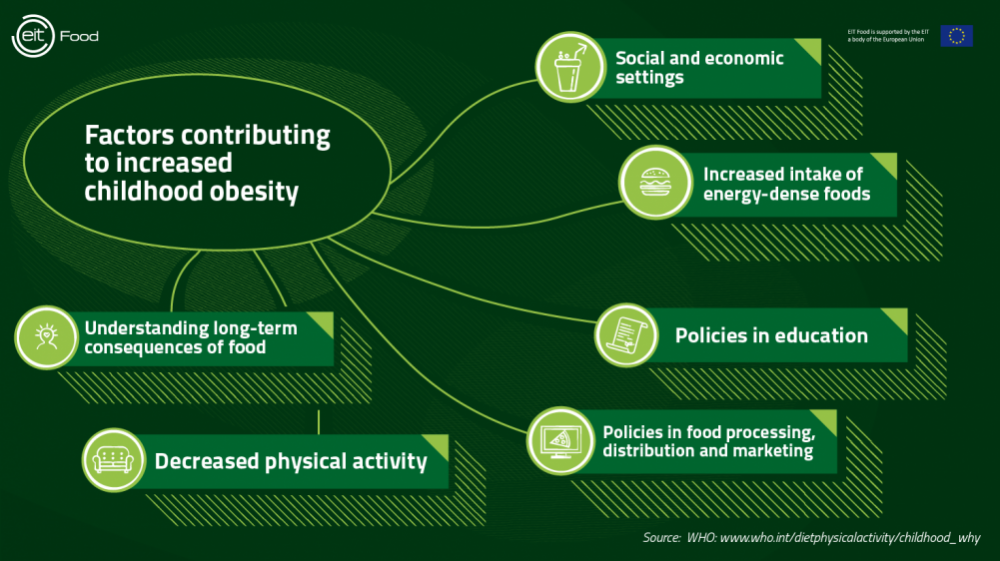

Among other biological and mental health considerations, factors acknowledged as possible causes of the increase in childhood obesity include (5):

- Diet: increased intake of energy-dense foods high in fat and sugars but low in vitamins, minerals and other healthy micronutrients.

- Exercise: decreased physical activity levels due to the increasingly sedentary nature of lifestyles, with each additional hour of television per day estimated to increase childhood obesity by 2% (4).

- Society: influence of social and economic development and policies in the areas of agriculture, transport, urban planning, the environment, food processing, food distribution, marketing and education.

- Environment: children and adolescents cannot choose the environment in which they live or the food they eat.

- Understanding: children have a limited ability to understand the long-term consequences of their behaviour.

Of course, each factor can combine with one or more of the others. It is also likely that the specific nature of each factor is influenced by social settings. For example, in societies where food scarcity has been a problem, parents may believe that the larger a child is, the better the parenting has been. These parents will increase children’s food intake where possible, which means that, if they are not adequately supported with advice about diets and nutrition, they may be particularly susceptible to increases in portion sizes.

Sometimes advice can seem conflicting too, adding a new layer of difficulty for parents – a problem because those who demand their children eat specific foods in specific ways can inadvertently promote overeating (6). Placing these high demands for eating behaviour and not responding to a child’s needs or desires can cause food rejection or picky eating (6), potentially leading to snacking or negative associations with meal times and healthy foods.

Of course, parents are not acting in isolation and those social settings are also heavily influenced by commercial interests, and the intense marketing of unhealthy food. In 2019 in the UK, when ITV and the campaign group Veg Power led a supermarket-supported advertising initiative to encourage children to eat more vegetables, they demonstrated the power such campaigns can have. A report on the “Eat Them to Defeat Them” initiative claimed that 650,000 children said they had eaten more vegetables as a result, and that every family in the UK ate an extra portion of vegetables per week during the campaign (7).

It's crunch time! The veg are coming and we need your help to #EatThemToDefeatThem ???????????????? pic.twitter.com/bczk9n6R6o

— ITV (@ITV) January 25, 2019

Groba believes that key messages may need to be slightly modified to be made relevant for certain regions if they are to be effective. For example, she points out that in southern Europe people are more likely to eat late, and in large family groups, whereas in northern countries there is less large-scale communal eating, and people tend to eat earlier.

The picture is further complicated by the fact that childhood obesity is not spread evenly across different social groups. Across Europe, we see that as deprivation increases, the number of children at a healthy weight decreases, and the number of children measured as overweight or obese increases (8).

Different beliefs and attitudes also have effects. In the UK, for example, parents of overweight and obese children often believe their children are a healthy weight. In one survey, the majority of children who were overweight but not obese were described as being “about the right weight” by their mothers (90%) and fathers (87%). Around half of parents of obese children (47% of mothers and 52% of fathers) also said their child was about the right weight (9).

In a recent episode of The Food Fight podcast (10), Dr Natalie Masento from University of Reading and Sarah Hickey from Guy's and St Thomas’ Charity discuss the current state of childhood nutrition in the UK and globally. Listen now to hear discussions about the impact of “food environments” and how physical and emotional surroundings can play a role in building positive habits.

Listen Now:

Given the complexity of the picture, it could be easy to become despondent. Professor Corinna Hawkes, the Director of the Centre for Food Policy at London’s City University, concedes that the poor quality of effective, coordinated initiatives across Europe in the past has been very disappointing.

However, she also notes that there has been huge progress in at least acknowledging it is a problem that needs to be addressed. “And there has also been a great leap scientifically in understanding it. We have a huge amount of data now, with a number of people having made important links with the data between obesity and physical activity.”

This is a reminder that there is ground for believing the problem will be solved. After all, it's worth remembering that despite the prevalence of obesity and overweight in southern Europe, some countries like Italy, Portugal, Spain and Greece have experienced a decrease in recent years (11).

What is the solution?

EIT Food Schools Network

If eating habits and behaviour are to be changed, then it’s important to tackle this issue early on. And one EIT Food project is doing just that. The EIT Food Schools Network is an educational initiative in Europe that includes EIT Food partners AZTI, Grupo AN, Queens University Belfast and the universities of Helsinki, Reading and Warsaw. It links EIT Food to existing national school programmes across Europe, developing a portfolio of approaches within educational settings which could be used to improve children’s relationships with food.

We know that eating in a healthy way doesn’t just mean ‘eating your greens’. However, children’s ideas about food, and their understanding of what healthy eating entails, isn’t necessarily the same as adults – they have much more limited experiences and often lack the knowledge to make informed choices. The ultimate goal of the EIT Food Schools Network is to change the habits and perceptions of children in relation to what it really means to eat healthily by helping them to discover more about food and nutrition in fun and interesting ways.

Programmes are tailored for different age groups. For pre-school children, there is an education tool focused on the acceptance of healthy food and self-regulation; for primary school children nutritional education, and for secondary school children various approaches designed to positively influence food choice and reduce food waste. You can join the conversation yourself on Twitter.

EIT Food Childhood Obesity Workshops

Groba’s series of childhood obesity workshops are currently looking at five big ideas that could be – individually or in combination with each other – foundations for new solutions:

1. Targeting the solution

Schools and digital platforms have been seen as ideal places on which to focus messaging, but what about, for example, workplaces? Or pharmacies? Might it be possible to make interventions in homes? And how might we persuade our institutions like hospitals and schools to cooperate more closely?

2. Different solutions for different settings

Local authorities and health services need greater powers to tackle the factors leading to obesity in their area. Might there be ways to encourage the formation of consortia between different players – scientific societies, universities, local government, industry and business, startups – to share expertise and costs?

3. Using Design Thinking

Might it be time to try a radically different approach to interventions in child obesity? They are often approached from a scientific perspective, that uses a logical assessment of what we know will have an impact, the activities we should partake in, and the food choices and food formulations that are ideal to prevent or reduce obesity. One alternative approach would be to use the human-centred principles of design (12) – empathy, observation, ideation, prototyping and testing - to better understand people's aspirations, motivations, day-to-day goals and how these relate to healthier choices and behaviours.

4. Analysing gut microbiota

Thanks to new, sophisticated means of analysing gut microbiota (communities of microorganisms, including bacteria, yeasts, viruses and protozoa, in the gastrointestinal tract) its importance in shaping health and disease outcomes has become more apparent. Could this offer an entirely new route, or an approach that might work in conjunction with others, to combat childhood obesity?

5. Working with the food industry

Reformulating foods has the potential to reduce obesity levels in a cost-efficient way, such as by reducing calories from sugar and saturated fat in processed foods. So how can the next generation of food innovators best be encouraged and supported to enable the food industry to create healthier and more sustainable products?

The EIT Food community is uniquely placed to enable collaboration across the food industry to solve highly complex issues like childhood obesity, where solutions must take into account interrelated causes. We work with food manufacturers to share information and insights, and to support actions they may take in respect of the problem.

Groba believes that “We can't pretend anymore that we're going to reverse childhood obesity just by reducing the sugar content in one or two food products.” In keeping with her belief that fixing "one or two food products" won't solve the whole problem, EIT Food favours a "food systems" approach to obesity, which looks at the whole farm-to-fork food chain, and promotes change in the way that food is produced, processed and consumed.

The role of the food industry

It is important to recognise that removing or changing ingredients can be extremely challenging. This may be through specific actions, such as changing recipes. Food reformulation is often a realistic chance to provide healthier and more sustainable food choices to consumers, but it also presents technological problems. Most ingredients in processed foods are there for a purpose, and adding or removing ingredients can change the whole safety, texture and taste of the food. However, people are finding innovative solutions.

In another episode of EIT Food’s The Food Fight podcast (13), Eschar Ben-Shitrit, founder of animal-free meat producer and EIT Food RisingFoodStar Redefine Meat, explained that while an enjoyable taste was essential if a food product was to be popular, “taste is not a single thing.” Taste, he went on, is related to texture, and Redefine Meat has found that as long as their products are close to meat in terms of delivering the texture of meat, the taste improves.

Listen Now:

SEFARI, the Scottish Environment, Food and Agriculture Research Institutes, has done interesting work to show that some synthetic compounds could be replaced by natural ingredients with several benefits. Adding herb extracts to cooking oil delayed the degradation of the oil and made it healthier; beetroot acted like a preservative when added to burgers, and boosted the antioxidant qualities (14).

Changing recipes does not have to impact the enjoyability of food for consumers, or sales for food producers. Danone has been working for several years to improve the nutritional qualities of its foods, reducing, for example, the sugar and fat content of its Brazilian children’s brand by 32% and 35% respectively. Some 82% of its sales volumes are now compliant with its nutritional targets (15).

Bridget Benelam of the British Nutritional Foundation agrees that the causes of childhood obesity “span the whole of society, which means we need to make changes in many different areas. This is very challenging,” she says. “In particular, as we face very difficult economic circumstances with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, it's important to note that children from families on low incomes are at higher risk of obesity, and so tackling poverty is key to reducing childhood obesity.”

Lorena Savani, EIT Food's Innovation Programme Manager, also highlights on the Food Fight podcast (13) that in the medium and longer term, evolving technologies may also play a role in reducing obesity. Take, for example, 3D food printers, which could quickly and cheaply deliver food tailored to individuals’ specific dietary needs.

There is increasing evidence that our unique genetic makeup can be a cause of obesity (3), which means that the ability to personalise our food according to our genes could help many of us to reduce and even avoid it altogether. The advantage of being able to personalise food for individual needs will become more important. Cheap, easy-to-use 3D food printers could allow us to do just that.

And of course as we acquire more tools and knowledge to fight the problem, education and awareness-building will be ever-more important. Having initiatives like the EIT Food Schools Network in place will be invaluable.

If childhood obesity is to be reduced around the world, a vast range of people and organisations will need to work in unity to fight the problem, and devise innovative approaches that will genuinely engage people of all ages.

Get involved

EIT Food is driving this kind of change by bringing together experts from dozens of different areas, and by helping to launch new, original initiatives. We want to deliver positive change by enabling conversations, and the exchange of ideas and information. If you have experience and/or expertise in this area, and would like to be involved in finding new solutions, please reach out to us. Mercedes Groba can be contacted at mercedes.groba@eitfood.eu.

You can also attend the third EIT Food Innovation Forum, which takes place online November 5-6 2020. Featuring experts from the agrifood industry, EIT Food partners, researchers and agents of innovation, the forum will use roundtable discussions, workshops, a masterclass and networking to examine current issues in the agrifood system, with a particular focus on targeted nutrition. If you would like to attend, you can register here.

Further reading

- FAO: Broken food systems and poor diets are increasing rates of obesity

- WHO: Obesity and overweight

- New Food: Learning to love veg

- The Food Schools Network: Improving children’s relationships with food

Sources

- WHO: Taking Action on Childhood Obesity

- WHO: Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative

- Krushnapriya Sahoo, Bishnupriya Sahoo, Ashok Kumar Choudhury, Nighat Yasin Sofi, Raman Kumar, Ajeet Singh Bhadoria (2015): Childhood obesity: causes and consequences

- Patricia M Anderson, Kristin E Butcher: Childhood obesity: trends and potential causes

- WHO: Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health

- Dr Leann Birch, Jennifer S Savage, Alison Ventura, Influences on the Development of Children’s Eating Behaviours: From Infancy to Adolescence

- Veg Power, ITV: Eat them to defeat them campaign evaluation 2019

- The most recent data show that overweight and obesity prevalence for children living in the most deprived areas is greater than it is for those living in the least deprived areas: in England, 25.8% compared to 18.0%; in Scotland, 25.1% compared to 17.1%; and in Wales, 28.5% compared to 22.2%.

- NHS Digital: Health Survey for England 2017 Adult and child overweight and obesity

- EIT Food: The Food Fight Podcast: Childhood nutrition and health: are we doing enough?

- WHO: Latest data shows southern European countries have highest rate of childhood obesity

- Human-centred design

- EIT Food: The Food Fight Podcast: Should producers be responsible for making food healthy?

- Sefari: Food Reformulation: Making Processed Foods Healthier

- Danone: Better Products

More blog posts

Protein Diversification Think Tank BLOG