Battle of the Labels: How should the EU update food packaging labels to encourage healthier choices?

Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods can be an effective way to educate and communicate with the public about food and health. By law, nutrition labels in the European Union must include the rates of a variety of components, including calories, protein, fat, and salt, in a data table on the back of a food package. In addition, companies may voluntarily choose to disclose other data such as fibre, vitamins, and minerals, or to display nutrition information on the front of a food package as well.

Food labels are particularly important as they are a regulated, trustworthy resource for consumers to understand what they are purchasing and eating. According to a university research study, the majority of consumers, across education levels and ages, reported checking food labels at least occasionally when shopping. In addition, a 2018 study in the journal Appetite demonstrated that nutrition labels help customers make better food choices; when shoppers compared nutrition labels of products, they tended to purchase significantly healthier options.

Food labelling legislation was first standardised across the European Union in 2011. Since then, the European Commission has been updating regulations to ensure uniformity across EU countries, while being mindful of national and cultural differences. The most recent change to the EU’s food labelling laws, which took effect in 2016, provides guidelines for food packaging including minimum font sizes, mandatory disclosure of allergens such as soya and gluten, and clear origin information for meat.

Several proposals from national public health agencies and activists to standardise nutrition labels’ visual format across the EU have gained traction in recent years. Proponents argue they may help increase health and transparency in the food system. However, how exactly those labels should look remains a subject of debate within the EU.

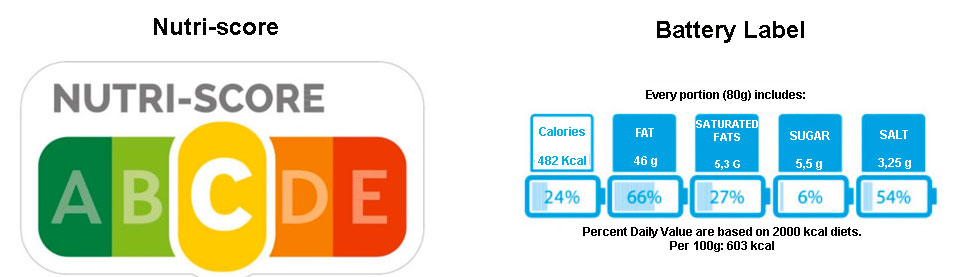

One food label that has become increasingly common in Europe recently is the Nutri-Score labelling system, the French public health agency, in 2017. The system assigns a colour and letter — ranging from green ‘A’ on the left to red ‘E’ on the right — to evaluate the nutritional value of foods. Food products scored ‘A’ are highly nutritious, whereas food products scored ‘E’ are least nutritious. Since its origin in France, the label has since been recommended by public health authorities in Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. Some major food companies, including Nestlé and Danone, have also voluntarily adopted Nutri-Score in some European countries.

The Nutri-Score is calculated by assigning point values to seven nutritional attributes. This includes four ‘negatives’ of calories, sugar, saturated fatty acid, and sodium; and three ‘positives’ of protein, fibre, and percentages of fruits, vegetables and nuts. Points are calculated per 100g of food. Positive points are then subtracted from negative points, and the resulting number is converted into an A-E score.

However, authorities in some countries, notably Italy, oppose the Nutri-Score system nationally and on an EU-wide level. In a query to the European Parliament, Italian MEP Mara Bizzotto argued that the Nutri-Score does not evaluate the foods in the context of a balanced diet, and ‘Made in Italy’ products like Parmigiano Reggiano and extra-virgin olive oil earn too-low scores. “Italian producer associations regard the Nutri-score system as discriminatory, since it gives distorted and incomplete information regarding nutritional values, arbitrarily classifying as dangerous many Mediterranean food products,” Bizzotto writes. “This is simply misleading consumers, rather than providing accurate and impartial information about agri-food products.”

In response, Italian health authorities have created the Battery Label, which focuses on five components: calories, fat, saturated fats, sugar, and salt. Rather than offering a score, the Battery Label lists the quantity of each component and calculates the percentage of the daily recommended value provided by the food.

Other skeptics of Nutri-Score focus on how the label ranks protein. Meat products can earn high rankings on Nutri-Score, leading to a final ranking of A or B that indicates nutritiveness. However, critics suggest the label ignores the importance of sustainability, including the environmental effects associated with meat production, such as high greenhouse-gas emissions associated with livestock.

Despite this, the current version of Nutri-Score remains solely dedicated to guiding consumers on the nutritional value of food, and is not obliged to adjust scores depending on sustainability. “Perhaps in a few years, we will do another label that will integrate also climate-friendly products and the short supply chain,” said Greens MEP Michèle Rivasi, who supports the current label.

Interpretive vs. Informational Labels

Research suggests ‘interpretive labels’ such as Nutri-Score are significantly more effective than ‘informative labels’ such as the Battery Label. In a 2018 study in the journal Nutrients, respondents across 12 countries ranked the perceived nutritive value of three products, firstly with no label and again with one of five common front-of-package labels. The five label options included the Nutri-Score and a reference intake label (RI) that closely resembles the Battery Label.

While all respondents were more likely to rank the products correctly with any label versus none at all, the increases in correct responses with Nutri-Score labels were higher than any other label option. The reference intake labels led to the smallest increase, a result that suggests they are significantly less effective at educating and influencing healthier consumer choices than Nutri-Score labels.

“Except for nutrient-specific numeric [front-of-package labels], which are purely informative, all other labels entail some level of interpretation of nutritional content through the use of colours, graphics, and/or textual elements and can be considered as interpretive labels,” the researchers explain. “Nutrient-specific labels providing only numerical information have been consistently found to be poorly understood by consumers, in particular by those with low educational levels, as they entail a high cognitive workload to interpret.”

As a consumer, you can use your purchasing power to support companies displaying clear nutrition information, simply by opting to buy products with the label that helps you best understand the product on the shelf. There are also advocacy groups petitioning the European Commission to adopt standardized labels, including a group called Pro-Nutriscore that has amassed 85,000 of the 1 million signatures needed to spur a response from the Commission.

To learn more about food labels, read the article here about an EIT Food project that is improving the communication of health claims on food packaging.

More blog posts

Farming in Europe: the changing landscape of food production

Discover a Day in the Life of a Product Line Work